|

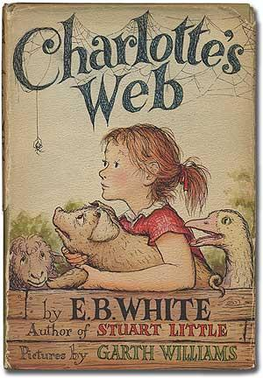

| Charlotte's Web (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In my entry for the last day of winter, in "Meeting Maida", I recalled how I nearly got snookered by a lookalike reprint of the first edition of A Time to Kill, only to find, on close examination, a reference to Grisham's second book in the dust jacket text.

Today I can offer another example of how, dealing with first editions, you never really know what you know until you do some research. But mostly I want to remember E.B. White (1899-1985), one of his collaborators, and the classic books they made together.

Today is the 103rd birthday of the great illustrator, Garth Williams, one of whose many, brilliant, works is E.B. White's 1952 classic kids' tale, Charlotte's Web. (HBB remembers him on today's Birthdays page.) Charlotte's Web is a brilliant tale, charming and wise. White began writing it in 1949, and some have suggested he was working through some unresolved personal issues with it. White wasn't having any of that, though:

Since E. B. White published Death of a Pig in 1948, an account of his own failure to save a sick pig (bought for butchering), Charlotte’s Web can be seen as White's attempt "to save his pig in retrospect". White's overall motivation for the book has not been revealed and he has written: "I haven't told why I wrote the book, but I haven't told you why I sneeze, either. A book is a sneeze".

I picked up my copy in one of my hoovering-up auction forays at The Salvation Army where, when it comes to books, you can count on them to sort the wheat from the chaff, send the chaff to their stores, and sell the wheat, by the bushel.

Hardcover? Good. Dist jacket? Price-clipped, but otherwise, OK. Some wear on the wrapper at the top and bottom of the spine. Otherwise, quite good. Copyright page said 1952, but not a stated first edition. So I kept it. It’s a classic. Someone will want it, I thought. It’ll be an easy sell. I’m gonna need those early on.

I got second thoughts. I've had it up on my shelf, thinking I would keep it myself. It has just enough dust jacket wear, I thought every time I looked at it, to make it the profit margin risible.

But when Garth Williams' birthday rolled up on the HBB events calendar today, I thought, OK, here's a hook. Let's see if we can get a bite.

Williams was an inspired illustrator with a knack for bringing his subjects to life. He was, also, either more than a little naive at times, or possessed of a sly sense of humor (or, perhaps, it just goes to show how far racial paranoias can be stretched):

In 1958 Garth Williams wrote and illustrated...The Rabbits' Wedding. The illustrated picture book, aimed towards children aged 3 to 7, depicted animals in a moonlit forest attending the wedding of a white rabbit to a black rabbit. In 1959, the book became the center of a controversy, with Alabama Senator E.O. Eddins and Alabama State Library Agency director Emily Wheelock Reed as the key players. Senator Eddins, with the support of the White Citizens' Council and other segregationist, demanded that the book be removed from all Alabama libraries because of its perceived themes of racial integration and interracial marriage. Emily Wheelock Reed reviewed the book and, finding no objectionable content, determined it was her ethical duty to defend the book against an outright ban. A battle ensued between Reed and her supporters and the segregationist faction in the legislature. In the end, the book was not banned outright, but rather placed on special reserve shelves in the state library agency-run facilities. Libraries who had purchased their own copies were not required to make this change.

Since the controversy, there has been more critical analysis done on the book. Some have noted the obvious logic of illustrating the rabbits with two different colors so the reader might tell them apart more readily. Others, in their quest to depoliticize the book, have claimed a perception of the black and white motif as, perhaps, a reference to yin and yang (i.e. male and female, though, inconsistently, the color-to-gender associations in the book are reversed). About the controversy, Williams stated, "I was completely unaware that animals with white fur, such as white polar bears and white dogs and white rabbits, were considered blood relations of white beings. I was only aware that a white horse next to a black horse looks very picturesque." Williams said his story was not written for adults, who "will not understand it, because it is only about a soft furry love and has no hidden message of hate."

Garth Williams

I pulled down my Charlotte, not seriously looked since I bought it, and set to work. First stop? Abe.com, for my money the best book research site around for a first-cut valuation.

How did Williams come to illustrate the book? By happy accident, it seems, and one that changed the course of the artist’s life:

Williams worked making lenses at a war plant, applied for work as a camouflage artist, contributed war-effort posters to the British-American Art Center in New York, and brought his portfolio around to the major publishing houses. He drew for The New Yorker for a mutually unfulfilling period of time. Then, in 1945, he received his first commission as an illustrator, from editor Ursula Nordstrom of

E.B. White at The New Yorker.

The augurs were well as I opened Abe: a first ed, first printing, with unclipped dust jacket, inscribed by the author, was listed for $31,500. I started scrolling down from the stratosphere, entry by entry, towards earth.

When I got down into the three-digit price range, I slowed my descent. I noticed one- without the dust jacket- for $350. That seemed a bit high. Something else rang a bell, something I could not pull into an articulate thought, but I looked under my copy's dust jacket.

The covers were not the same. Mine had the Williams dust jacket art printed on the hard cover.

"Time to look at Fedpo," I thought. First Edition Points is a good website for sussing out modern classic first editions- the ones liable to be mutton dressed as lamb in these days of massive press runs, three-digit printings, and copycat reprints. It has illustrations of the things one should look for to verify a true first ed, kind of like a Wikihow entry.

"Well, damn," was my next thought. They had an entry for White's Stuart Little, but not Charlotte's Web. I backed out, typed in a new search string, and ended up at Modern First Editions Blog. They had a very informative, and disheartening, entry, from which I learned that my copy was a reprint of the first edition, and a post-1963 reprint at that. Harper & Brothers, which published Charlotte in 1952, changed its name to Harper & Row in 1962, and that was the name on the dust jacket, book spine, and title and copyright pages (even though the Library of Congress number, now largely replaced by the ISBN, began with "52": another way one can be fooled in a hurry).

Modern First Editions Blog, whose owner patiently and informatively vetted many readers' copies in the comments section to Charlotte's Web, revealed more information about H&R printings, and with each nugget I watched my copy come rushing toward me, past to present. A comment one reader made about the promos on rear dust jacket made another light bulb go off for me, and I had my A Time To Kill moment all over again: the first White book promoted on the jacket is Stuart Little.

No probs, that came out in 1945. The second? The Trumpet of the Swan, the one White YA book I never really connected with, though, today, I couldn't think why.

That became clear, as did the age of my Charlotte's Web, when I looked up Trumpet. A 14 year-old, I was past that sort of story when it was published- in 1970.

In 1933, White and his wife, Katherine, a New Yorker editor and gardening writer, bought a coastal farm in Maine, to which they eventually moved permanently. For Charlotte's Web's 60th anniversary, NPR passed along a story:

White's experiences in his own barn that led him to the story of Charlotte and her web. "One of the pigs he was raising died," Sims says, "and while he was carrying the pails of slops every day to the replacement pig in the barn, he noticed there was a spider attending its web every day, expanding the web, rebuilding what had happened the night before, and then one day he saw that it had spun an egg case."

When White had to go back to New York City, he cut down the spider's egg case and took it with him. Eventually the baby spiders hatched, and after that, White finished spinning his now-famous tale. And in 1970, he sat down in a studio to record the narration.

"He, of course, as anyone does doing an audio book, had to do several takes for various things, just to get it right," Sims says. "But every time, he broke down when he got to Charlotte's death. And he would do it, and it would mess up. ... He took 17 takes to get through Charlotte's death without his voice cracking or beginning to cry."

In another NPR story from 2008, when a Publisher's Weekly poll named Charlotte's Web the best children's book ever published in America (it made #1 again in 2012), Fresh Air contributor Maureen Corrigan, reviewing a book about Charlotte's Web, ended with this:

White's own later understated estimation of his work is the most touching. In old age, when he was suffering from Alzheimer's, White liked to have his own essays and books read to him. Sometimes White would ask who wrote what he was listening to, and his chief reader, his son Joe, would tell him, you did, Dad. Sims says that White would think about this odd fact for a moment and sometimes murmur: Not bad.

So that's how I spent a chunk of my day. The book turned out not to be worth much. I'm keeping it. Sometimes, happily, there’s more to a book’s value than what I can sell it for.

It’s been a good day.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We enjoy hearing from visitors! Please leave your questions, thoughts, wish lists, or whatever else is on your mind.