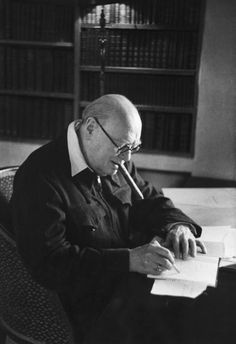

Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill (1874-1965)

Soldier, politician, writer

He was the nephew of a duke, and lived like one for ninety years. The one catch was that, while well-off, he didn’t have the landed income of a duke.

He turned to writing to fill the endless gaps in his budget. It was the ideal career, allowing him to use his connections to get sent interesting places, to write about interesting things. The resulting cascade of articles and books advanced his standing as a man of affairs, and being in the thick of things made for wonderful opportunities to shift from reporter to newsmaker, then back again.

Winston Churchill was commissioned an officer in the Hussars in 1895. He was twenty-one years old and earned 300 pounds a year- about $21,000, today. To live like a gentleman-officer, though, he reckoned he needed another 800 pounds per annum.

His mother granted him an allowance of 400 pounds, and he made up the rest running tabs. He was, after all, the son of a famous politician and nephew of a peer.

Journalism was his salvation. Standards being different then, he sought commissions as a war correspondent while seeking postings to the most interesting conflicts in the British Empire’s high water decade. He saw the Cuban Revolution of 1895 as a newspaper correspondent and published two volumes on his experiences in Egypt and the Sudan by 1899.

Established- he thought- as a celebrity author/soldier, Churchill ran for Parliament at 24, and lost. Just in time, The Boer War broke out. He snagged a correspondent’s gig, hopped a boat, and managed to get himself out to the front, captured, imprisoned, freed, and then, in a fine bit of swagger, demanded and obtained the surrender of 52 Boers with his cousin, the new Duke of Marlborough.

He returned home after eight months, produced two books and more articles, went on a lecture tour of America, and won election to Parliament, where he sat, with only a couple of breaks, for sixty-two years. For thirty of those years, Churchill held cabinet rank fourteen different posts-, including nine years as prime minister.

In 1899, Churchill learned there was already a writer called Winston Churchill: an American, a near contemporary who was selling his novels in staggering quantities. So the British Churchill penned a note to the American one:

“Mr. Winston Churchill presents his compliments to Mr. Winston Churchill, and begs to draw his attention to a matter which concerns them both. He has learnt from the Press notices that Mr. Winston Churchill proposes to bring out another novel, entitled Richard Carvel, which is certain to have a considerable sale both in England and America. Mr. Winston Churchill is also the author of a novel now being published in serial form in Macmillan's Magazine, and for which he anticipates some sale both in England and America. He also proposes to publish on the 1st of October another military chronicle on the Soudan War. He has no doubt that Mr. Winston Churchill will recognise from this letter -- if indeed by no other means -- that there is grave danger of his works being mistaken for those of Mr. Winston Churchill. He feels sure that Mr. Winston Churchill desires this as little as he does himself. In future to avoid mistakes as far as possible, Mr. Winston Churchill has decided to sign all published articles, stories, or other works, 'Winston Spencer Churchill,' and not 'Winston Churchill' as formerly. He trusts that this arrangement will commend itself to Mr. Winston Churchill, and he ventures to suggest, with a view to preventing further confusion which may arise out of this extraordinary coincidence, that both Mr. Winston Churchill and Mr. Winston Churchill should insert a short note in their respective publications explaining to the public which are the works of Mr. Winston Churchill and which those of Mr. Winston Churchill. The text of this note might form a subject for future discussion if Mr. Winston Churchill agrees with Mr. Winston Churchill's proposition. He takes this occasion of complimenting Mr. Winston Churchill upon the style and success of his works, which are always brought to his notice whether in magazine or book form, and he trusts that Mr. Winston Churchill has derived equal pleasure from any work of his that may have attracted his attention.”

The American Churchill saw his name entirely swallowed up by the British one over the next decade, and, after World War I, gave up writing.

From 1929 to 1939 Churchill was out of office, and out of favor with his party. He wrote endless articles- always getting top dollar from his friends among the British press lords, while mining the family archives for more books. His 1905-06 life of his father did well, his 1930s biography of the first Duke of Marlborough, in four volumes, was a success. He wrote most of a four-volume history of the English-speaking peoples during that decade, though events held up its publication until the mid-1950s (he was working on its final chapter the night Hitler invaded Poland).

Churchill led his nation to victory in World War II, then sat down to write about it. His five-volume history of the first war- The Great Crisis- had done well, despite being described by one rival as “Winston’s autobiography disguised as a history of the universe.” Having been in on the action, Churchill saw no reason not to lap the track again. The resulting History of the Second World War capped his literary career and won him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

His last decade was a well-earned, if boring, retirement, as events left him behind and ill-health stalked him. His 40th book appeared in 1961; his eleventh stroke finally carried him off shortly after his 90th birthday. Winston Churchill's total output- published and in private correspondence- has been estimated at somewhere near thirteen million words. His Complete Speeches, covering the years 1897 to 1963, contain 5.2 million alone.

Naturally, his son- who carried on alternating between journalism, war, and politics, with less success- undertook his father’s biography, producing two volumes before he died in 1968. Settling upon the idea of adding “companion volumes” of documents and letters, the final version- at 24 volumes- has been certified by Guinness as the longest biography in the history of the world. At 9.2 million words, it still trails its subject’s amazonian output and took a third of its subject’s life to complete.

To be a Churchill is now a subject and a career. His daughter, Mary, became biographer of her mother and published a number of other works on her parents. His grandson, Winston, covered the Six Day War in 1967, wrote a book about it, and went into Parliament. Late in life, he too published a book about his grandfather. During his time as a Member of Parliament, Churchill visited Beijing with a delegation of other MPs, including Clement Freud, a grandson of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Freud asked why Churchill was given the best room in the hotel and was told it was because Churchill was a grandson of Britain's most illustrious Prime Minister. Freud responded by saying it was the first time in his life that he had been "out-grandfathered".

The total number of books about Churchill is thought to be somewhere near a thousand.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We enjoy hearing from visitors! Please leave your questions, thoughts, wish lists, or whatever else is on your mind.