Lindsay Thompson

Things are written now to be read once, and no more; that is, they are read as often as they deserve. A book in old times took five years to write and was read five hundred times by five hundred people. Now it is written in three months, and read once by five hundred thousand people. That’s the proper proportion.

-Elizabeth, Lady Eastlake, pioneering British woman literary critic (1809-1893)

A book is the only immortality.

-Rufus Choate, American lawyer, orator, and politician (1799-1859)

The term “bestseller” first appeared in a Kansas City paper in 1889. The first bestseller list, in The Bookman, began six years later. In America until the late 19th century, the term described mostly outlaw books; copyright laws were so lax that any American or European author whose work did well could expect his income to be bled away pirated editions.

While the tighter legal regime of the 20th century enriched authors, making it possible for a sort of feedback loop of sales boosting books to bestseller lists, thus boosting more sales and raising a book’s rank in the lists, thus boosting sales still more (after which lies paperback and movie rights and mass market deals with big box national book chains and, now, online sellers), there’s never been any set, universally-agreed on criteria for deciding what’s a bestseller.

As much as anything, the credibility of a best-seller’s source rubs off on it, so that a “New York Times bestseller” is a better thing to be than that of, say, a plumbing fixtures trade magazine, and The Times’ list remains The One To Get On.

That list was launched in October 1931, and aggregated sales data from New York City (five fiction and four nonfiction titles), expanded to eight big cities shortly after and fourteen by decade’s end. In those days the quality book market was found in the book departments of the great department stores in major urban areas.

Data collection improvements made it possible to switch to a national list in 1942, based on reports from 22 cities. Since then best-seller lists have proliferated into genres and subgenres.

The exact method for distilling the data is a tightly guarded secret lest efforts be made to game the results, though that has not stopped anyone from trying. There are books purporting to explain how it’s done.

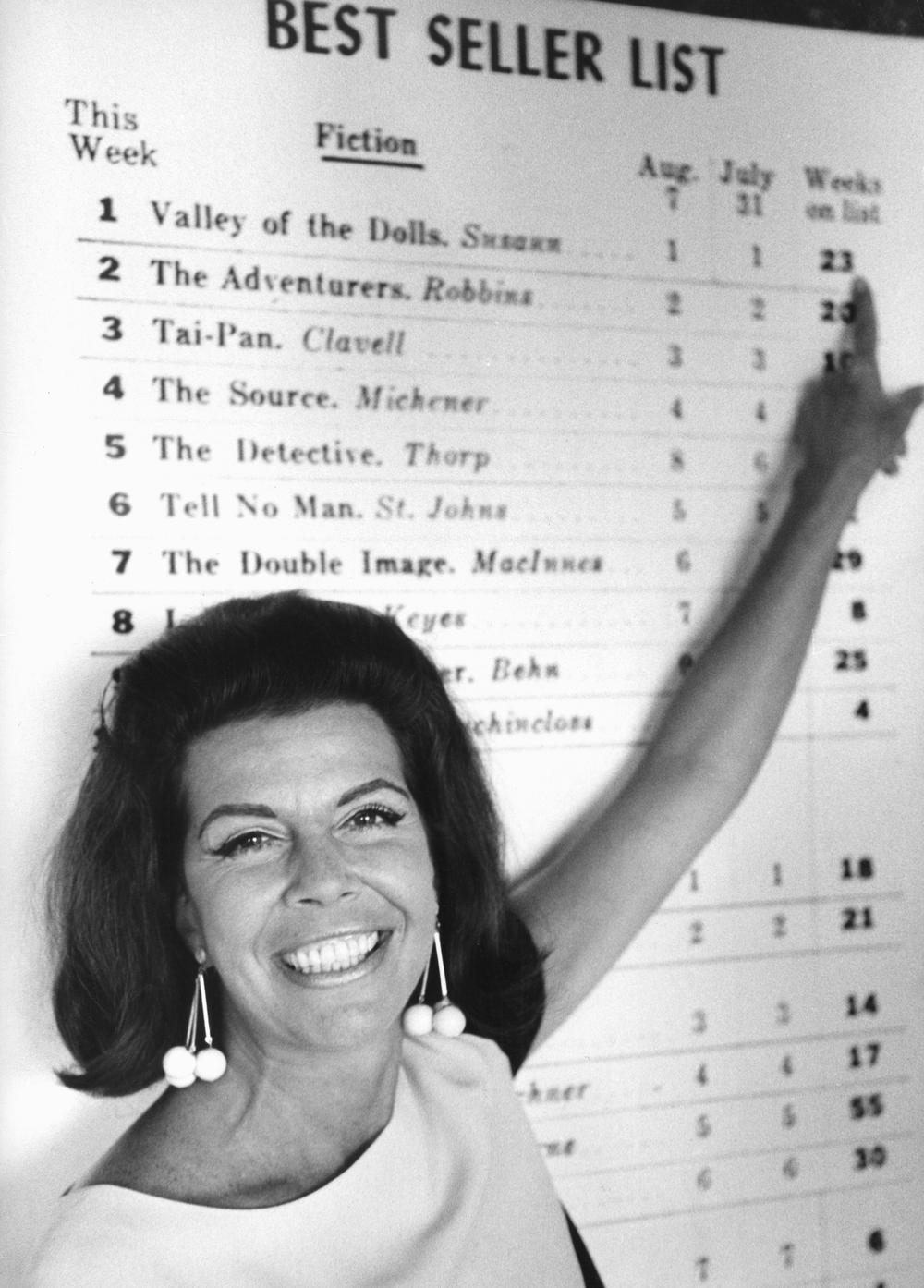

Jacqueline Susann, who- with her publisher- invented the modern sales campaign, tried to boost her opening Times ranking by sending out 1500 copies of Valley of the Dolls to influential people. USA Today founder Al Neuharth and PBS guru Wayne Dyer routinely bought thousands of copies of their books, directly or through entities they controlled.

The Times now flags books reporting large bulk sales, which has opened yet another avenue for politicians to beat up on the paper. Three 2016 candidates for President- Carson, Cruz and Trump- were accused of trying to boost their campaign biography sales through complex remaindering and buyback schemes with their publishers and campaign operations, and each tried to turn the story into proof of the liberal Times’ vendetta against conservatives and their ghost writers.

Other authors have sued The Times, claiming their works were wrongly left out.

The vagaries of statistics can mislead, too. A “fast” bestseller, which moves a lot of copies n a short time, can vault up the list ahead of books that, selling more slowly over a longer period, end up selling way more copies.

Publishers use pre-publication promotional campaigns to build a head of steam and boost initials sales; some even offer authors bonuses and royalty boost for quantifiable efforts to get, and keep, their books on the list. Since bestseller status is a steroid for author speaking fees, the incentives to hold thumbs to the scale is heavy indeed.

These collateral revenue incentives may be the result of an interesting effect noted in 2004 by a Stanford University business professor. As Stanford Business reported,

Each week millions of readers look at the New York Times best-seller list to see what everybody else in the country is reading. And as soon as a title hits the list, booksellers typically push the book to the front of the store and slash its price by as much as 40 percent.

So it seems reasonable to assume that once a book makes the list its sales will really take off—if not for the lower price then because readers might view best-seller status as a sign of quality or because they don’t want to miss the action. According to the Business School’s Alan Sorensen, an assistant professor of strategic management who has studied the effect of best-seller lists on sales of hardcover fiction, the majority of book buyers seem to use the Times’ list as a signal of what’s worth reading. Relatively unknown writers get the biggest benefit, while for perennial best-selling authors such as Danielle Steel and John Grisham, being on the list makes virtually no difference in sales.

“There is an effect, but it’s small—much smaller than most people would have expected,” says Sorensen, who studied sales records for 2001 and 2002. “What’s remarkable is there is this dominant downward [sales] trend,” he says, describing the typical sales path over time in the fiction titles he studied. Most sales occur soon after a book hits the shelves and gradually peter out. “If anything, what appearing on the [best-seller] list does is not so much cause your sales to increase from one week to the next, but rather to decrease at a slower rate.”

Of course, looking at best-sellers alone wouldn’t prove that any week-to-week sales changes were caused by the list itself. To answer the causal question, Sorensen needed a comparison group: books that sold well but somehow missed the list. So he looked at data from Nielsen BookScan, a sales monitoring service that tracks retail sales of books across the nation. Unlike the New York Times, which samples sales from only some stores, Nielsen BookScan captures most actual sales.

Consequently, Sorensen found differences in the two lists. In fact, in the two years he studied, Sorensen found 109 different books that failed to make the Times list even though Nielsen reported they sold more copies than other titles on the Times’ list. Thus, if Sorensen saw sales rise on the Nielsen BookScan data the week following that same title’s appearance on the New York Times list but saw no similar increase for a different top-selling Nielsen book that wasn’t on the Times list, he inferred that something about the appearance on the Times list caused the subsequent jump in sales.

Based on these comparisons, Sorensen estimates that previously best-selling authors got the least benefit from being on the New York Times list, while unknowns had the greatest jump in sales. On average, he estimates, appearing on the Times list might increase a book’s first-year sales by 13 to 14 percent, but for first-time authors sales probably would increase by an impressive 57 percent. And for established authors like Danielle Steel or John Grisham whose every novel seems to become a best-seller, “the list has no discernible impact on sales,” writes Sorensen.

This pattern, he says, suggests the best-seller list primarily tells consumers what may be worth reading. “It’s free advertising for new authors who make it to the list,” he says. With a well-known author, on the other hand, people don’t need a best-seller list to help them decide whether to buy the book.

Careful to isolate the best-seller list from other likely causes of higher sales, Sorensen also looked at the famous “Oprah effect,” the stunning way being chosen for Oprah Winfrey’s on-air book club immediately catapults a title onto the best-seller list. Though reluctant to name numbers because there were few Oprah titles in the sample, Sorensen says the Oprah effect is “many times bigger” than the best-seller effect.

Looking at sales of individual titles is fun, but for economists, says Sorensen, a more interesting question is the effect of best-seller lists on overall product variety. If best-seller lists are indeed generating extra sales, are those sales stolen from other books? Or are those extra sales literally extra sales, bought by people who wouldn’t otherwise have bought any book? “It’s a really hard question, and I don’t have the ideal data for answering it,” concedes Sorensen. But he has indirect evidence suggesting that being on the list does indeed generate extra sales. If he’s right, everyone but the perennially best-selling authors and their publishers may have a little bit less to grumble about.

So it seems reasonable to assume that once a book makes the list its sales will really take off—if not for the lower price then because readers might view best-seller status as a sign of quality or because they don’t want to miss the action. According to the Business School’s Alan Sorensen, an assistant professor of strategic management who has studied the effect of best-seller lists on sales of hardcover fiction, the majority of book buyers seem to use the Times’ list as a signal of what’s worth reading. Relatively unknown writers get the biggest benefit, while for perennial best-selling authors such as Danielle Steel and John Grisham, being on the list makes virtually no difference in sales.

“There is an effect, but it’s small—much smaller than most people would have expected,” says Sorensen, who studied sales records for 2001 and 2002. “What’s remarkable is there is this dominant downward [sales] trend,” he says, describing the typical sales path over time in the fiction titles he studied. Most sales occur soon after a book hits the shelves and gradually peter out. “If anything, what appearing on the [best-seller] list does is not so much cause your sales to increase from one week to the next, but rather to decrease at a slower rate.”

Of course, looking at best-sellers alone wouldn’t prove that any week-to-week sales changes were caused by the list itself. To answer the causal question, Sorensen needed a comparison group: books that sold well but somehow missed the list. So he looked at data from Nielsen BookScan, a sales monitoring service that tracks retail sales of books across the nation. Unlike the New York Times, which samples sales from only some stores, Nielsen BookScan captures most actual sales.

Consequently, Sorensen found differences in the two lists. In fact, in the two years he studied, Sorensen found 109 different books that failed to make the Times list even though Nielsen reported they sold more copies than other titles on the Times’ list. Thus, if Sorensen saw sales rise on the Nielsen BookScan data the week following that same title’s appearance on the New York Times list but saw no similar increase for a different top-selling Nielsen book that wasn’t on the Times list, he inferred that something about the appearance on the Times list caused the subsequent jump in sales.

Based on these comparisons, Sorensen estimates that previously best-selling authors got the least benefit from being on the New York Times list, while unknowns had the greatest jump in sales. On average, he estimates, appearing on the Times list might increase a book’s first-year sales by 13 to 14 percent, but for first-time authors sales probably would increase by an impressive 57 percent. And for established authors like Danielle Steel or John Grisham whose every novel seems to become a best-seller, “the list has no discernible impact on sales,” writes Sorensen.

This pattern, he says, suggests the best-seller list primarily tells consumers what may be worth reading. “It’s free advertising for new authors who make it to the list,” he says. With a well-known author, on the other hand, people don’t need a best-seller list to help them decide whether to buy the book.

Careful to isolate the best-seller list from other likely causes of higher sales, Sorensen also looked at the famous “Oprah effect,” the stunning way being chosen for Oprah Winfrey’s on-air book club immediately catapults a title onto the best-seller list. Though reluctant to name numbers because there were few Oprah titles in the sample, Sorensen says the Oprah effect is “many times bigger” than the best-seller effect.

Looking at sales of individual titles is fun, but for economists, says Sorensen, a more interesting question is the effect of best-seller lists on overall product variety. If best-seller lists are indeed generating extra sales, are those sales stolen from other books? Or are those extra sales literally extra sales, bought by people who wouldn’t otherwise have bought any book? “It’s a really hard question, and I don’t have the ideal data for answering it,” concedes Sorensen. But he has indirect evidence suggesting that being on the list does indeed generate extra sales. If he’s right, everyone but the perennially best-selling authors and their publishers may have a little bit less to grumble about.

Five years later, however, e-books introduced a new wild card into the bestseller list mix: favoring the instant-gratification buyer, and, therefore, well-known authors, e-book sales in 2010 comprised a major chunk of new books by bestselling authors. CBS Money Watch found,

The speed at which e-books are taking over the publishing industry is truly breathtaking. The same Independent article throws around the statistic that 35% of the 1 million copies of Jonathan Franzen's Freedom were e-books. That's 350,000 copies sold.

An article in The New York Times that mistakenly fixated on the price of some e-books also contained the impressive information that Ken Follet's latest thousand-page bestseller sold 20,000 copies in the e-book format during its first seven days on sale. Selling 20,000 copies of anything would get an author onto one of the top spots on the New York Times bestseller list.

These numbers tell us something important about ebook sales: they are heavily weighted toward the big-name, frontlist authors. E-book sales may only be projected to reach 10% of total book sales in a couple of years because of the size of the industry's backlist and the huge percentage of "long-tail" sales.

The engine of change in the industry sits in the head, among the top-selling authors and items. These are the books that were super-charged in sales by the emergence of the superstores and the industry's improved logistics that allowed bestsellers to be heavily discounted in supermarkets and big-box retailers like Costco. The six big publishers chased those sales as they migrated out of bookstores which is one reason that Barnes & Noble and Borders are limping along today.

Transforming the top end of the business changes the whole of the business. The current economics of publishing is front-loaded. In a previous generation, the business was ballasted by backlist but no longer. Like a movie studio, book publishers thrive on sugar-rush of big ephemeral hits.

An article in The New York Times that mistakenly fixated on the price of some e-books also contained the impressive information that Ken Follet's latest thousand-page bestseller sold 20,000 copies in the e-book format during its first seven days on sale. Selling 20,000 copies of anything would get an author onto one of the top spots on the New York Times bestseller list.

These numbers tell us something important about ebook sales: they are heavily weighted toward the big-name, frontlist authors. E-book sales may only be projected to reach 10% of total book sales in a couple of years because of the size of the industry's backlist and the huge percentage of "long-tail" sales.

The engine of change in the industry sits in the head, among the top-selling authors and items. These are the books that were super-charged in sales by the emergence of the superstores and the industry's improved logistics that allowed bestsellers to be heavily discounted in supermarkets and big-box retailers like Costco. The six big publishers chased those sales as they migrated out of bookstores which is one reason that Barnes & Noble and Borders are limping along today.

Transforming the top end of the business changes the whole of the business. The current economics of publishing is front-loaded. In a previous generation, the business was ballasted by backlist but no longer. Like a movie studio, book publishers thrive on sugar-rush of big ephemeral hits.

Fast forward another five years: last year, e-book sales fell some fifteen percent after several years of flattening numbers. Where once they were poised to swallow publishing whole, they are now settling into a permanent niche for certain types of readers, in certain reading situations.

But the distorting effect on sales numbers remains, simply because the per-unit cost of an e-book is nil compared the same book in a dead tree format. Sales prices can be slashed to generate bigger numbers and move up the list.

Even taken at face value, bestseller lists are not a reliable quality judgment on a book’s staying power or literary merit. Classics- Shakespeare, Dante, George Eliot, Henry James- aren’t measured at all. For one thing, a book out of copyright protection is fair game for any publisher, letting cheap editions proliferate from old plates and older translations: it is impossible, for example, to read a Jules Verne novel in English. American publishers played merry hell with the adaptation to English, altering, or omitting, dialogue, skipping boring scientific bits, and sexing up the adventure quotient for target audiences like young boys.

Bestsellers, another report has it,

have gained such great popularity that it has sometimes become fashionable to purchase them. Critics have pointed out that just because a book is purchased doesn't mean it will be read. The rising length of bestsellers may mean that more of them are simply becoming bookshelf decor. In 1985 members of the staff of The New Republic placed coupons redeemable for $5 cash inside 70 books that were selling well, and none of them were sent in.

Oh, brave New World, Miranda warned us in The Tempest. Of the making of books, there is no end, we are warned in Ecclesiastes. Being a writer calls for a level of reckless hope and optimism to rival that of elderly gardeners, so unlikely is it that a book will be long, or well, remembered.

Yet for those who find succor in old books, there are joys uncounted in rediscovering the works, often great and timeless, of authors whose reputations have long been lost or mislaid. As an exercise, I offer this article. Here- from the archives listings compiled by Hawes Publications- are the top ten titles (and how long they’d been there) from The New York Times’ bestseller list for February 5, 1967. Some wrote schlock, some were literary lions, some were steady, midlist producers. Some were veterans and some had brilliant early innings cut short by death. All sought the the immortality of publication.

Here they are, the few, the happy few- seven men and three women- in the fifth week of the new year, a long time ago:

1. Robert Crichton, The Secret of Santa Vittoria (21 weeks)

Crichton (1925-1993) was a Purple Heart/Bronze Star winner, wounded at the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he briefly ran an ice cream factory outside Paris, graduated from Harvard with the 2000-strong, GI Bill-swelled Class of 1950, and set up as a freelance writer.

Crichton (1925-1993) was a Purple Heart/Bronze Star winner, wounded at the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he briefly ran an ice cream factory outside Paris, graduated from Harvard with the 2000-strong, GI Bill-swelled Class of 1950, and set up as a freelance writer.

He cranked out biographies for hire and articles about anything to support his growing family. His first book, The Imposter- about an actual, pathological identity faker called Fred Demara- was made into a film starring Tony Curtis.

The Secret of Santa Vittoria was a home run for Crichton, then 41. A tale of Nazi resisters in an Italian hill town, it spent fifty weeks on the bestseller list, including eighteen at #1. The all-star cast movie won a Golden Globe in 1969. Crichton’s second novel, The Camerons, was based on his great-grandparents and their family of Scots coal miners. Published in 1972, it, too was a best seller. He intended a sequel but never finished it. He didn’t need to.

Crichton spent the rest of his years writing articles when he felt like it, and died at 68. Biblio.com lists a first edition of The Secret of Santa Vittoria for $50.

2. Allen Drury, Capable of Honor (13 weeks)

A 41-year-old wire service reporter, Allen Drury (1918-1998) shocked the publishing world with his first novel, 1959’s Advise and Consent. Author Russell Baker, asked to read the manuscript, recalled his reluctance:

What lies I would be compelled to tell poor Allen ... The box weighed slightly less than a ton. The manuscript inside was typed not very well on long, legal-size paper. I took it home, ate, fixed a drink, sat down and with a heavy heart reached into the box for a fistful of manuscript. Good Lord! You couldn't put the thing down! I read half the book that night and finished it next day. My wife finished close behind, and the sight of her suppressing a tear at one point confirmed my hunch.

A political thriller set in the US Senate, Drury’s doorstop of a novel was a hit. It spent 102 weeks on the bestseller list and won the 1960 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, before being made into a successful, still-seen movie.

Drury spent the next decade writing sequels each rather worse than its predecessor, moving his characters around Washington and the larger stage of international affairs. Capable of Honor was the second of those sequels, anticipating the 1968 presidential election in a world beset by racial conflict and Soviet adventurism.

Drury wrote twenty novels in all, including several that indulged his interest in ancient Egypt. He was, however, an author with a following and thus a reliable base of buyers, and when he died in 1998 his books went promptly out of print.

A small publishing house began reissuing them in 2014. First editions of Capable of Honor run about $25 today.

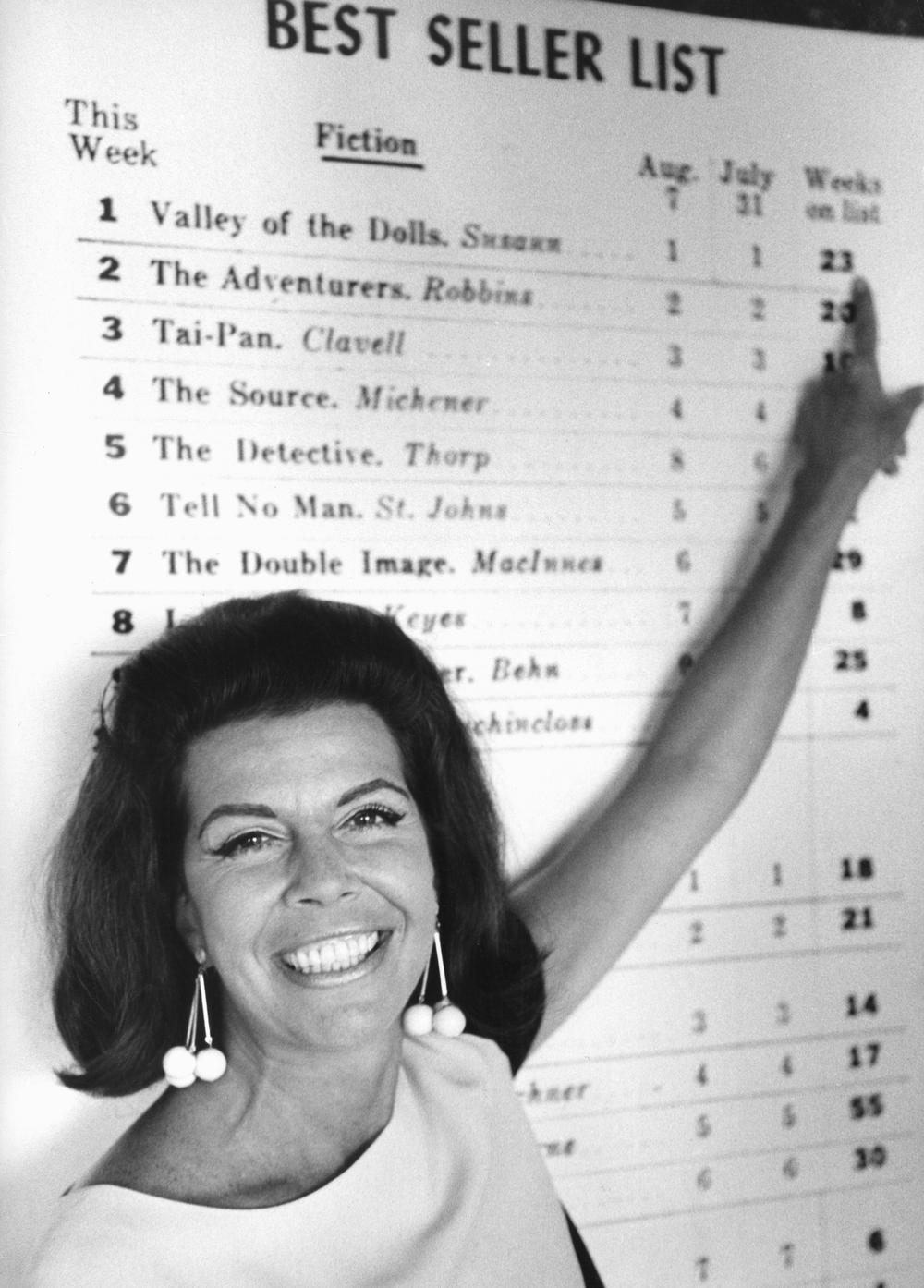

3. Jacqueline Susann, Valley of the Dolls (48)

An insanely ambitious failed actress, Jackie Susann (1918-74) was a depressed, pill-popping housewife with an autistic son, breast cancer, and a marginally successful TV producer/agent husband.

As soon as she got out of the hospital in 1963, she walked to Wishing Hill and made a pact with God. If He would give her only 10 more years, she promised God, “she would prove she could make it as a writer, as the number-one writer,” her husband recalled.

Writing 10 to 5 every day, Susann cranked out five drafts of what became Valley of the Dolls, a twenty-year postwar saga of life in and around Hollywood. Completely trashy and utterly compelling, Dolls was a money-spinner before it even came out in 1966- paperback and movie rights raked in $400,000- almost $10 million today.

An imaginative promotional campaign and Susann’s cross-county, barnstorming book tour steamrollered largely negative reviews. The book sold 35,000 hardcover copies and 1.7 million in paperback.

After nine weeks on the bestseller list, Dolls cracked #1 and spent 28 weeks there. By the time Susann died Dolls was in the Guinness Book as the bestselling novel in history, with 17 million copies in print.

Susann and God kept their bargain. She became the first writer to produce three #1 bestsellers in a row. She was bulletproof when it came to critics; when she sent out 1500 copies to taste-makers, Amy Fine Collins wrote in Vanity Fair, “Norman Mailer’s secretary replied that Mailer “won’t have time to read Valley of the Dolls.”

Fine drolly concluded,

This was an admission Mailer may have come to regret, because Susann consigned him to the fate of becoming Once Is Not Enough’s Tom Colt—a hard-drinking, pugnacious writer with a child-size penis.

In 2016 Susann’s publisher issued a fiftieth-anniversary edition of Valley of the Dolls. Worldwide sales are now somewhere north of 31 million copies, and spiraling into infinity, and beyond. You can find a signed first edition for $1250.

4. Rebecca West, The Birds Fall Down (15 weeks)

A half-English girl of 18 named Laura visits her grandfather, Count Diakonov, opulently exiled in fin-de-siecle Paris. Old Diakonov philosophizes amid malachite vases, cloisonne jardinieres, rosebushes made of coral, and furnishings to match. They are the sort of things that bloom at Parke-Bernet but choke a novel. In this milieu dialogue is uttered rather than spoken; at times you suspect it to be lifted stiffly from a Constance Garnett translation of some Tolstoy imitator. As Laura and her grandfather embark on a journey you can't help feeling that the story itself is going absolutely, if baroquely, nowhere.

But don't underestimate Dame Rebecca. The moment old Diakonov has left the house, an oddly intriguing note creeps into his garrulity. He is no longer muffled by too much interior decor. Furthermore, you sense that the author -- whose forte has always been the undomestic -- also feels liberated. Diakonov's words lose their stilts but not their grandeurs. His ruminations on why he was exiled, in what ways the French are decadent, and how to hunt the mountain cock, all flow together into the portrait of a totally unregenerate and rather irresistible reactionary.

And this monologue, however intriguing, is only an overture. Shortly after Count and granddaughter board the train, a stranger enters their compartment. He turns out to be Chubinov, an old friend now a terrorist, who warns that the Count is in great danger and that he, Chubinov, is himself on a mission of murder.

A monstrous conversation ensues, over 100 pages long, which in its simplest level turns the book into a breathtaking mystery. Much of the domestic clutter of earlier pages stands now revealed as clue to an insidious plot. But the two men on the train do far more than introduce a suspense mechanism. They exchange diatribes that become hypnotic. After a while their sustained, page-long outbursts begin to sound natural. Miss West has raised them from artificial convention to heightened reality. You question Carmen singing -- instead of speaking -- her love to Don Jose.

And with what bizarre but compelling arias Count and terrorist assail each other! In a foreword Miss West notes that the things they talk about, and indeed they themselves, are based on historical models. I find an overtone of superfluous apology in her statement. Fiction, if successful, doesn't need the corroboration of history. In fact it completes history by making it accessible to the imagination. "The Birds Fall Down" is marvelously successful wherever it combines two of her special talents: a pipeline direct to the Slav soul which produced her Yugoslav memoir, "Black Lamb and Grey Falcon"; and her intuition about the ambiguities of good and evil as shown in "The Meaning of Treason." The present novel, and most particularly the vast conversation which constitutes its core, marshals both gifts to stage a hair-raising duel of ideas.

What makes this duel an experience is precisely its excesses. Its barbaric length, its discursiveness, its untempered violence and unwonted warmths, its quintessentially Russian quality. The Count pits his absolutism against the terrorist's until Czar and Revolution are exalted into equally Byzantine ideals of cruelty and redemption.

But don't underestimate Dame Rebecca. The moment old Diakonov has left the house, an oddly intriguing note creeps into his garrulity. He is no longer muffled by too much interior decor. Furthermore, you sense that the author -- whose forte has always been the undomestic -- also feels liberated. Diakonov's words lose their stilts but not their grandeurs. His ruminations on why he was exiled, in what ways the French are decadent, and how to hunt the mountain cock, all flow together into the portrait of a totally unregenerate and rather irresistible reactionary.

And this monologue, however intriguing, is only an overture. Shortly after Count and granddaughter board the train, a stranger enters their compartment. He turns out to be Chubinov, an old friend now a terrorist, who warns that the Count is in great danger and that he, Chubinov, is himself on a mission of murder.

A monstrous conversation ensues, over 100 pages long, which in its simplest level turns the book into a breathtaking mystery. Much of the domestic clutter of earlier pages stands now revealed as clue to an insidious plot. But the two men on the train do far more than introduce a suspense mechanism. They exchange diatribes that become hypnotic. After a while their sustained, page-long outbursts begin to sound natural. Miss West has raised them from artificial convention to heightened reality. You question Carmen singing -- instead of speaking -- her love to Don Jose.

And with what bizarre but compelling arias Count and terrorist assail each other! In a foreword Miss West notes that the things they talk about, and indeed they themselves, are based on historical models. I find an overtone of superfluous apology in her statement. Fiction, if successful, doesn't need the corroboration of history. In fact it completes history by making it accessible to the imagination. "The Birds Fall Down" is marvelously successful wherever it combines two of her special talents: a pipeline direct to the Slav soul which produced her Yugoslav memoir, "Black Lamb and Grey Falcon"; and her intuition about the ambiguities of good and evil as shown in "The Meaning of Treason." The present novel, and most particularly the vast conversation which constitutes its core, marshals both gifts to stage a hair-raising duel of ideas.

What makes this duel an experience is precisely its excesses. Its barbaric length, its discursiveness, its untempered violence and unwonted warmths, its quintessentially Russian quality. The Count pits his absolutism against the terrorist's until Czar and Revolution are exalted into equally Byzantine ideals of cruelty and redemption.

Seemingly indestructible despite waves of health problems and endless rows with her son, the writer Anthony West (a 1913 argument with H.G. Wells led to lunch, a ten-year affair, and their son), West produced her last book at 91, in the year she died, and left several more for posthumous publication. In the bestseller list’s world of brass, she was all Tiffany to the end.

The Birds Fall Down can be found in a first edition, online, for about $25.

5. Mary Renault, The Mask of Apollo (12 weeks)

An English lesbian who moved with her partner to Durban, South Africa for tax exile on a $150,000 prize she won from MGM for her fifth novel, Renault found South Africa held a markedly more relaxed attitude toward same-sex couples than the UK. She found her niche writing meticulously researched novels set in the world of ancient Greece, where same-sex relations were part of the social milieu.

Renault (1905-1983) produced eight Attic novels between 1956 and 1981, spanning centuries and everyone from Theseus to Alexander the Great. Apollo, published when she was 61, was the fourth, set in the theatrical world of Athens in the time after the Peloponnesian War.

She was widely compared to Robert Graves for avoiding pedantry in the service of recreating a historically accurate past. The New York Times’ obituary underscored her skill in threading the most challenging of literary needles:

Other critics noted Miss Renault's insistence on lending her works historical accuracy without burdening them with boring pedantry, and it was also remarked that while dealing realistically but unsensationally with the life and mores of the Hellenic world, Miss Renault calmly treated bisexual and homosexual love as well as heterosexual love as universals in her fiction.

There were, however, those who noted Renault’s uneven handling of female characters, and her tough treatment of mothers. Some insisted she was actually a gay man writing under a pseudonym, so deft was her handling of relations between men.

For her part, Renault professed indifference: it was part of the way of a patriarchal world. As she aged and her books became oases for LGBT readers, however, she became more and more irked, then hostile, to a fan base she thought was trying to pigeonhole her. Renault remains popular, and in print, nearly thirty-five years after her death. Her companion of over forty years, Julie Mullard, survived her.

A first edition of The Mask of Apollo runs about $30; a signed first, $300.

6. Edwin O’Connor, All in the Family (16 weeks)

A Boston newspaper’s television critic, O’Connor’s was one of the shortest careers in the February 5 bestseller list. His first novel, The Last Hurrah (1956) introduced the title phrase into the American political lexicon for politicians who run one time too many. His second won the Pulitzer Prize in 1962.

All in the Family, the tale of a Kennedyesque political clan, was typical of O’Connor’s focus on the Irish-American experience. It was also his last book: thirteen months later he died of a stroke, only 49. His books, largely forgotten, run arond $25 in first editions.

7. Jan de Hartog, The Captain (3 weeks)

A Dutch merchant sailor and sometime actor, de Hartog published detective stories before World War II. A 1939 book on tugboat crews rescuing a stricken ocean liner, Holland’s Glory, was not only a rousing tribute to his seagoing nation but was seen by the Gestapo as a Resistance morale-booster. De Hartog was himself in the underground until 1943, when he was forced into hiding and then to flee to Britain.

When the war ended, de Hartog remained in the UK and switched to writing in English, earning him criticism and plummeting book sales his move to the US only made worse. But he adapted his life as easily as he did his tongue, producing scores of books and plays. One of the latter, Four Poster, was a Broadway hit debuted by Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy in 1951 and later made into the hit musical I Do! I Do!

The Captain was one of many novels in which de Hartog mined his wartime and seafaring experiences, a taut thriller about a Dutch freighter crew trying for safe harbor as Holland fell. De Hartog, who also became a Quaker and social justice advocate, died in 2002, aged 88. First editions of The Captain run $10-$20.

8. James Clavell, Tai-Pan (35 weeks)

A British citizen born in Australia who became an American, Clavell survived two Japanese World War II POW camps to return to Britain, marry, then emigrate to Hollywood. He became a successful screenwriter: The Fly, The Great Escape, and To Sir, With Love are among his credits.

He turned his hand to fiction in the 1960s, launching a series of novels set in Asia, past and present. Tai-Pan was the third of a series of six centered on a Scottish family of cut-throat Hong Kong traders. When the 1970s arrived, Clavell rocketed to superstardom with the miniseries of his samurai novel, Shogun.

Though he sold the rights to Tai-Pan for $500,000 in 1966, Clavell waited twenty years before the post-Shogun mania for hs work finally resulted in a movie.

Though most loved his novels for their sweep and historical vision, for Clavell they were imaginings of his ideal world. He was a major Ayn Rand fanboy, and saw the freewheeling capitalism and cheapness of life in Hong Kong as the way the world should be. Clavell died, at 70, in 1994. Still popular, Tai-Pan commands $50-$75 in first editions.

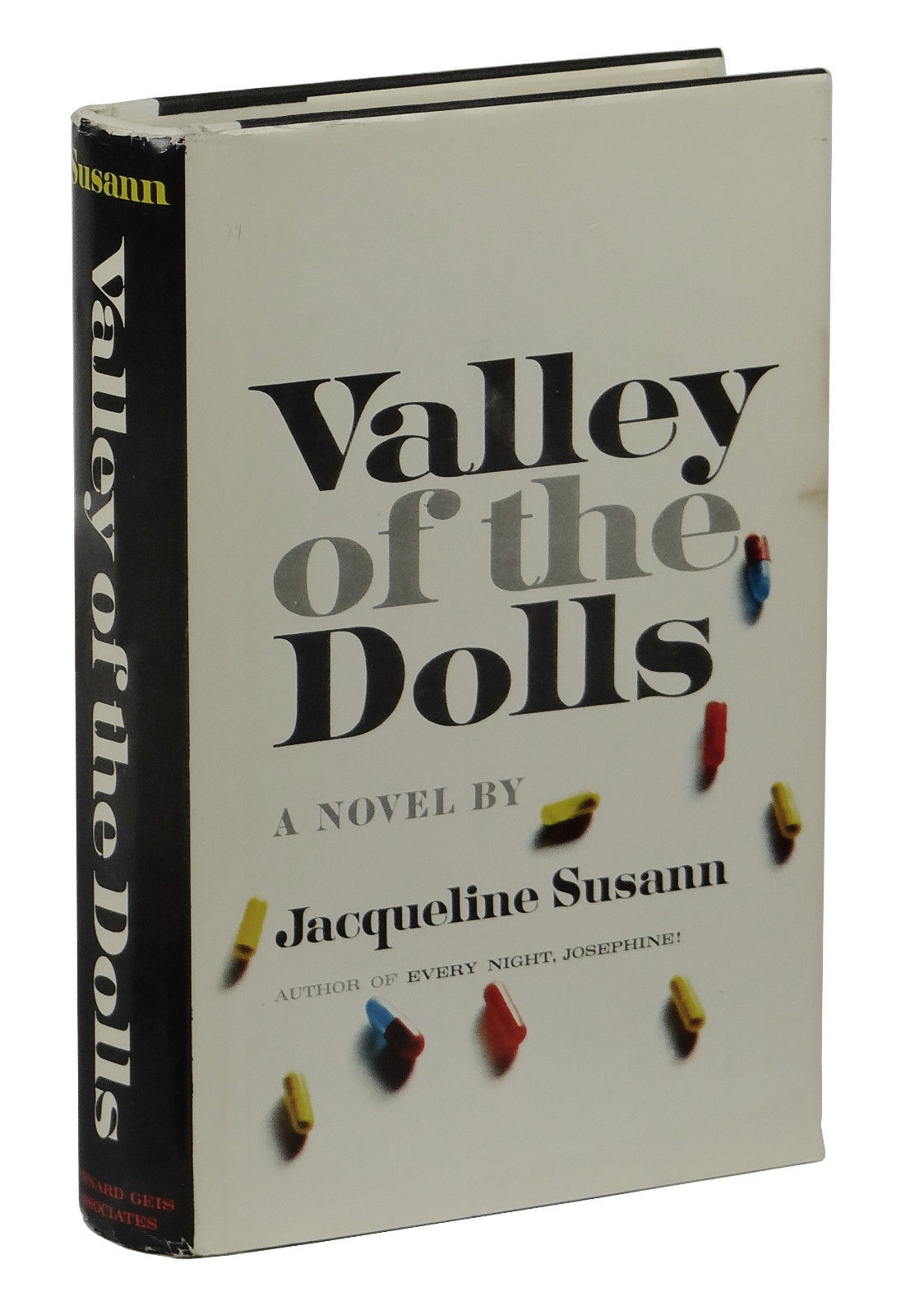

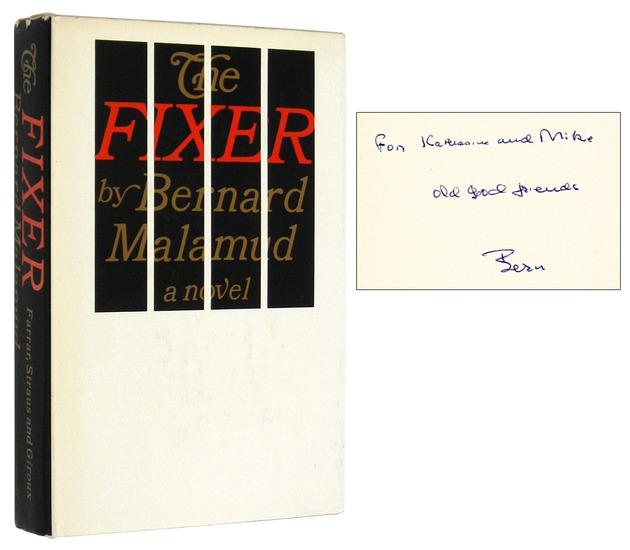

9. Bernard Malamud, The Fixer (19 weeks)

Like Rebecca West, Malamud (1914-1986) was a “literary” writer. The Fixer, his fourth of eight novels, treated anti-Semitism in Tsarist Russia. He was a slow writer, partly because he spent his career teaching at Oregon State University and Bennington College, but his books were always considered worth the wait by readers and critics.

Two years before his death, Malamud-widely considered the equal to Saul Bellow and Philip Roth- saw the film version of his baseball novel, The Natural, secure his place in American fiction. The pictured signed first edition above is $750.

10. John O’Hara, Waiting for Winter (4 weeks)

One of the leading writers of the post-war American scene, O’Hara (1905-1970) was in the winter of his career when this collection of short stories joined the best-seller list. He still holds the record for the most short stories published in The New Yorker (despite a fifteen-year boycott over a bad review of a 1949 novel), and a number of his novels remain in print.

He is also in the pantheon of The Library of America (though his inclusion led some grudge-bearers to use his inclusion as a cudgel to call for killing off the entire project for having no standards).

O’Hara’s strengths as a writer were his undoing as a person, however. He grew up the son of a wealthy Catholic doctor in a Protestant, smaller Pennsylvania city, and developed an acute sense of exclusion from the social elite. That alienation was only compounded when his father died, having frittered away the funds that would have sent young John to Yale.

He never got over it, and spent his career chronicling the F. Scott Fitzgerald social set and its postwar heyday, only through the window, or at club dinners as a member's guest. One critic noted that had O’Hara written The Great Gatsby, he’d have presented Daisy and Jay in bed, smoking a cigarette. There is neither nostalgia nor melancholy in his work.

O’Hara flaunted his wealth with Rolls-Royces and wives, but there was never enough success to slake his thirst. Yale denied him an honorary degree, President Kingman Brewster, said, because he asked for it so often.

He campaigned for a Nobel Prize. He composed an ostentatiously self-regarding epitaph and published it.

Still and all, O’Hara was a great writer, and his work has been dragged down, like Somerset Maugham’s, by the posthumous knifework of those with scores to settle. After forty years of his searingly insightful portrayals of the rich-but-not-necessarily-famous, the class to which he always sought entry wanted to close the ledger on O’Hara all accounts in balance. He died three years after Waiting for Winter. First editions can be had for as little as $15.

Charles Taylor’s excellent appraisal of O’Hara’s work comes to rest, as O’Hara did, with that epitaph:

It says on O’Hara’s tombstone in Princeton, New Jersey, “Better than anyone else, he told the truth about his time. He was a professional. He wrote honestly and well.” What’s appalling is that he composed it himself, one of those needy outbursts that have surely contributed to his underappreciation. Better than anyone else? No, and what kind of person would admit that even if he thought it? That should not keep us from admitting that the last part is not merely just but an understatement. Even in a moment of self-praise, O’Hara couldn’t help but be honest.

Lindsay Thompson owns Henry Bemis Books, an online rare book dealership, in Charlotte. He is a co-host of the Rare Book Cafe.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We enjoy hearing from visitors! Please leave your questions, thoughts, wish lists, or whatever else is on your mind.