Electric Lit considers ill-considered bargains:

“Lost are we, and are only so far punished,” Dante writes in Canto IV of the first part of his epic poem The Divine Comedy, “That without hope we live on in desire.”

In his debut novel The Gentleman, Forrest Leo crafts a story that hinges on these Dantean elements of confusion, punishment, and romantic longing. Lionel Savage, the narrator and protagonist, accidentally sells his wife Vivien to the devil and embarks on a strange and comical journey through Victorian London to get her back. He relays his trials and travels in the form of a memoir, executed and edited by Hubert Lancaster (a cousin of Savage’s missing wife), who provides footnoted commentary throughout.

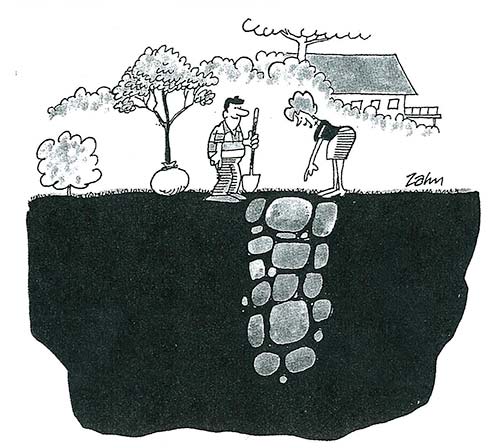

Such double-sided narration — through both Savage’s first-hand account and Hubert’s numerous annotations — wedges a kind of distraction into the story, as the two voices often diverge. “Lost are we” comes to mind as an adequate description of the readers’ (and characters’) experiences. And in Dante’s world, being lost means being deeply susceptible to waywardness and despair. Romantic desire becomes unquestionable, as it does for Savage: his one ungovernable aspect, untouchable by the instruments of hell. Dante wields an uncanny ability to characterize and represent change as it manifests in people. Leo, presumably a long-time student of Dante, knows this better than anyone. He employs Dante’s same sense of mutability and unpredictability. And like his predecessor, Leo has a whimsical gift: he has given Dante a key place in The Gentleman — as Satan’s gardener.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We enjoy hearing from visitors! Please leave your questions, thoughts, wish lists, or whatever else is on your mind.